It wasn’t much of a house. One of those places slapped together in the 1950’s by someone with very little money and access to castoff or cheap materials. Two bedrooms, a kitchen-dining area, and a living room paneled with tongue-and-groove wood where every piece was a unique roadmap of decay and insect damage, all shiny with shellac. Nevertheless, the place kept the weather out and sat on the lower end of 25 acres of pasture and woodland. It became the homely dream for a couple with rural Oregon roots and looking to escape with their three sons from suburban Seattle. They rolled up the driveway in the summer of 1960 with their belongings piled on an old one-ton Chevy truck. By 1962 there were four boys sharing one bedroom, the two oldest in a bunk bed, another in a twin bed under the window, a third wall occupied by the newborn in his crib, a shared dresser along the remaining side. The father eventually poured a new slab and doubled the reach of the house with a new bedroom, family room, and utility area. A barn, chicken coup, and hog house were added. The couple spent a large portion of their able years raising boys and keeping that place together.

Even with the improvements, it wasn’t much of house. Yet the adjoining property on two sides was unoccupied, and the neighbors on the third side had a boy who became friends with the eldest son. NO TRESPASSING signs were unknown and unnecessary. The boys became wildlings, roaming freely over pastures and ridges. They traveled far beyond the reach of artificial lines drawn onto a map of ownership, sometimes spending nights out with a campfire and cotton sleeping bag. Like all wild things, they didn’t know they had gone feral. Nor did they take their freedom for granted. It was a state of being. Akin to breathing. Fawn lilies and fence lizards and fossilized wood. Soaring red-tailed hawks on a blue-sky day. The nighttime comings and goings of blacktail deer inscribed by tracks and droppings. This was the natural order of things.

The boys grew up and scattered across the state and beyond. The father died in 2018. She hung on for as long as she could, then eventually had to live with the youngest son. She left the living world in 2023 as the house and fences continued to slide into various states of disrepair.

***

It was never much of a house, but as the eldest son I had to shoulder my memories and a responsibility to my family to sell the place. It went up for sale in January when winter rains slid off the steep hillside and surfaced in the pasture and yards. In our family, muddy jeans and stuck rubber boots and wet dog smell were the natural order of things. Akin to breathing. Surely someone could see the potential, imagine this place for what it had been to the wildling sons and parents who had raised them. But a sagging house and an equally sagging real estate market conspired against the powers of memory and imagination.

We dropped the price steadily with no results. September was drawing to a close. The rainy season was imminent, and with it would come the end of real estate season. I have not developed fluency in another language. However, somewhere along the way I managed to learn how to communicate with old houses. On a late September evening I sat on the back porch gazing past the chicken coup, through the sagging fences, and upward onto the hillside where big-leaf maples were beginning to transition to yellow amid somber conifers. I had a sense that the house was grieving. So I turned to it and spoke. You know, we’re all learning how to let go here. You need to let go, too. Two days later we had our first serious offer. Over the next four weeks the minefield of a real estate transaction had been negotiated. The house was giving itself over to a young couple with kids, building skills, and energy. Perfect.

It isn’t much of a house, but on the morning of Halloween Eve I signed off on our end of the sale. For two years we had been disbursing and disposing of six-decades of accumulation by my parents, that post-depression rural couple who kept everything that came into their lives just in case someone might need it. Even after the piles that had gone to family members and friends of family members and thrift stores and recycling and sometimes even the dump pit, a few clean-out chores remained. I drove past the empty mailbox and east to Mather’s Market for a few gallons of diesel. Then back to the house and up the gravel driveway, through the gate at the parking area, and into the pasture. There waited a pile of ash limbs, broken fence rails, pieces of old plywood, and chunks of rotten lumber, all of it topped off with the broken headboard from the bed that Mom and Dad moved here with.

As if on cue, the rains of October came in earnest, a slashing sideways torrent out of the southwest. I pulled on new rain gear, beat up leather boots, and a pair of deerskin gloves with a hole in one finger. Shook a half-gallon of diesel beneath a big piece of plywood where the center of the heap remained dry. Touched it off with one those windproof lighters that looks like a tiny blowtorch. The fire, aided and abetted by fossil fuel and wind, leapt quickly to life. With the newborn flames basting my face like a rotisserie chicken, I remembered being out here with Dad after Parkinson’s had begun to riddle his nervous system. He sat motionless on a stump staring into a crackling inferno and told me how much he loved to burn. There’s something purifying about it.

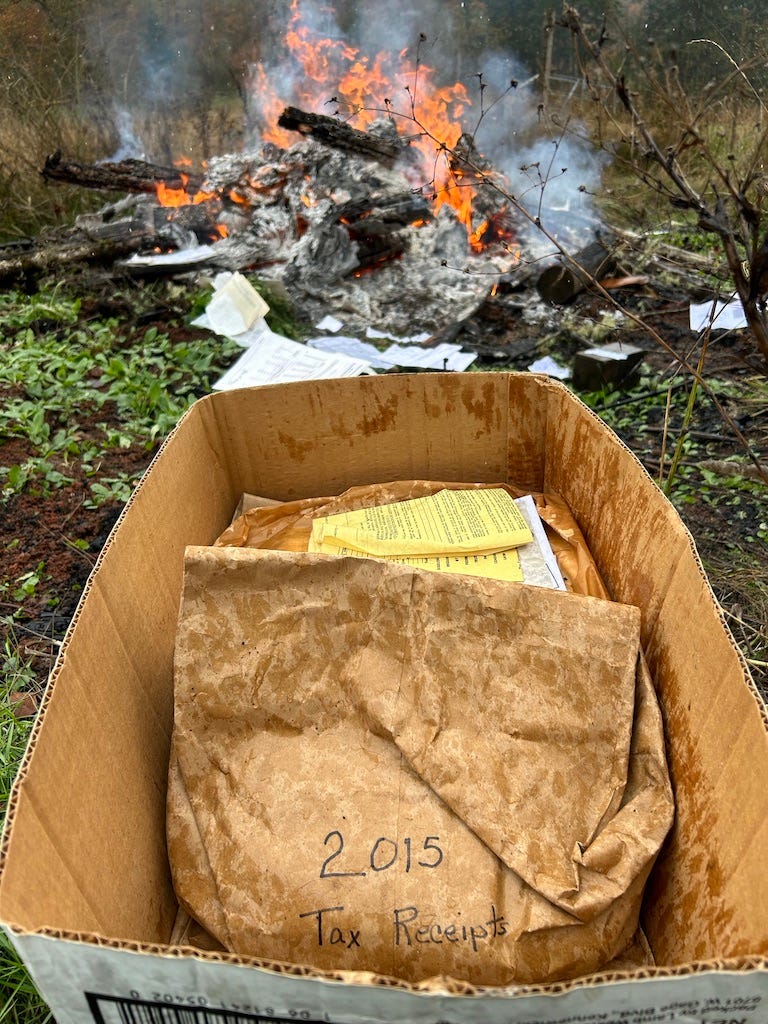

The carport was now empty save three boxes of Mom’s papers. I’d already sorted through them and extracted anything that might have had historical value. We could have paid to have the documents shredded. But we’ve always been a DIY family, and the papers had been left to feed into the burn pile. The fire was so hot I couldn’t stand close. From the upwind side I began scattering in the loose white sheets. Some of them caught the wind and fluttered into the droop of last summer’s dead grass. Taxes going back to 2012 had been organized by year into brown grocery bags labeled with a black marker. I am my mother’s son, and briefly considered saving the bags. There was a small piece of blue paper with a cookie recipe in Grammy’s handwriting. Pausing, I hoped that it was already in the family cookbook and tossed it in. Physical and emotional exhaustion from two years of cleaning out have hardened me in ways I don’t admire.

When all the papers were in the fire they needed to be stirred to fully combust. Paper is amazingly resilient to burning when burning is the desired outcome. We didn’t want anyone’s identity stolen, not even Mom and Dad’s, whose own ashes are now spread hither and yon around the fruit trees and garden and across the hillside that sweeps upward beyond the pasture. By now the embers had reached pig-roasting stage. I was beginning to worry about the health of my new rain gear. A fence rail, cracked and gray and encrusted with lichens, gave me the distance I needed to prod the half-black sheets into flame.

Suddenly I couldn’t do it any longer. The heat, exhaustion, and grief coalesced into a force that can only be called soul-crushing. I wanted to cry but couldn’t. Instead, I stepped backward and planted my ass in the dead grass, falling onto my elbows. Into the downpour I screamed Go ahead and steal our f*&^ing identity!!

Go ahead. Take it. Place a dark slice of us beneath your tongue. Let it dissolve like an ashy communion wafer. Maybe somewhere in the space where your soul hides like a fall seed you’ll feel freedom germinate and rise like smoke to meet the rain. You might begin to know the wildness of roots deeply anchored, or the wrench of having them unearthed. And somewhere beneath it all there might be the fertile soil of gratitude. For new October grass pressing upward between dead stems. For the accumulation of memory. Because after the flames have collapsed to ash that’s all you’ll tote away.

It wasn’t much of a house …

A quick plug for our 2024 The Nature of Gratitude, a gratitude variety show at Unity of the Valley, with contributions from poet Jorah LaFleur, writers Eric Alan and Melissa Hart, and musical interludes by Halie Loren, Beth Wood, and Don Latarski. This event will be in support of the nonprofit Center for Community Counseling.

Sunday, November 17, 3:00-430 p.m.

3912 Dillard Rd., Eugene OR 97405

Thank you, Tom. A beautiful benediction and recessional for what may not have been much of a house but was a cool dugout and crucial home plate for all you Titus players.

I can feel the heat of that fire.

As far as love goes, that house was a mansion. Thank you, Tom, for writing this.