I leave town with dawn spilling rosewater over the eastern ridge, the thermometer sitting at a pleasant 60 degrees. I’m not kidding myself—the temperature today is heading toward the century mark. When my family and I returned to the Willamette Valley almost exactly 30 years ago, the joke was that no one put their raincoats away until Fourth of July weekend. July used to be the month that kicked off the freewheeling relief of summer after a spring of seemingly incessant dishwater skies. Times have changed. This July we are already tipping over the edge into what has now become our season of anxiety. Of finger-tapping. Of wildfire watching.

Other changes have come this summer. When Mom passed last August, the deed to her uncle’s house and property in the heart of the Coast Range was transferred to Kim and me. This change of ownership is a landmark that exists mainly on pieces of paper shuffled by the hands of bureaucrats. Paper is flammable. In the real world of sweat equity, the kind you pay into by mowing, replacing dry rot and windows, keeping the spring water flowing, sweeping cobwebs and mouse turds, pulling bracken growing beneath the blueberries, and putting up enough firewood to push back against the cold fingers of winter dampness that press inward through drafty uninsulated walls, I’ve “owned” the place for years. And now I get to pay the property taxes.

Despite all the work, the Johnny Gunter place has settled in through my pores, seeping into aging muscles that sometimes ache with the physicality of stewarding rural property, finding its way even into the curves of my ribs and the heart they enclose. In the most fundamental sense, the property has come to own me, along with a host of fellow plant and animal inhabitants who preceded my European ancestors by millennia.

This is the spirituality of place that is so easily romanticized. Yet spirituality is the mystical pool from which emotional and physical realities eddy upward. Today the specter of an early July heat dome rises above the land like Nanahuatzin, Aztec god of the Sun, who seems to be pissed off at being back at his desk after a long holiday weekend. My thoughts have returned to fire—to the certain knowledge that wildfire is as much a part of this landscape as needled boughs sweeping into every canyon and draw, alder leaves scattering sunlight into tannin creeks, and the salmon-egg cling of Red Huckleberries ripening on the bush.

The reality of fire doesn’t leave me sitting on the porch with fingers curled loosely on my thighs, trying to enter a deep meditative state. Instead, I choose to bust my ass in what may ultimately become a futile endeavor—mitigating the possibility that this last Gunter family place, nestled as it is within a crazy convolution of coastal mountains and canyons that carry the light and the dark of 140 years of heritage, will burn. The prospect of fire is part of the grit load carried by this sacred river of connection. Fire awareness drives the sweat stains and scratched arms and sun-beaten skin that are part of maintaining a “defensible space.” And what if, after all that, the place still burns? As Mom told us when the Holiday Farm Fire swept down the McKenzie River Valley toward our childhood home, save the family pictures and papers. To hell with the rest of it. She was, at her deepest level, a practical woman.

When I arrive at the house, Swainson’s Thrushes are sending up misty tendrils of song from the conifers above the meadow. This spring the Barn Swallow family moved back into the garage after a year away. They chitter and slice their way into a mud-cup nest plastered to a rafter, feeding their nearly fledged young. Inside the house, I open doors and windows and place a box fan at the door to suck cool morning air inside and drive out that decaying-old-house mustiness. A short drive to search for native wild blackberries brings me hard up against a red and black sign placed by Sierra Pacific Industries. They are the new timber kid in the valley, the outfit who bought out Seneca-Jones and is now my next door neighbor. CLOSED TO PUBLIC ENTRY DUE TO EXTREME FIRE DANGER. More wildfire anxiety. I return to the house with two blackberries in my picker and for this year let go of Grammy’s age-old goal of “a blackberry pie by Fourth of July.”

The scorching forecast will likely force the valley into an extreme fire alert, meaning a better than even chance that mowers and other power tools can’t be run. Opting for the hardest thing first, I pull out a gas-powered weed eater and start taking down the rangy dandelions and knapweed around the perimeters of the lumber piles, garage, mill shelter, house, and fences—all the places unreachable with a mower. This is a lot of perimeters. By the time I’m done, Sun is a hard white frown high in the southern sky. Time to retreat inside. Close up the house. Eat a leftovers lunch. Recoup my shortchanged sleep with a nap. But when I wake, the nap feels shallow, like a thin sheet stretched too tightly to constitute deep rest.

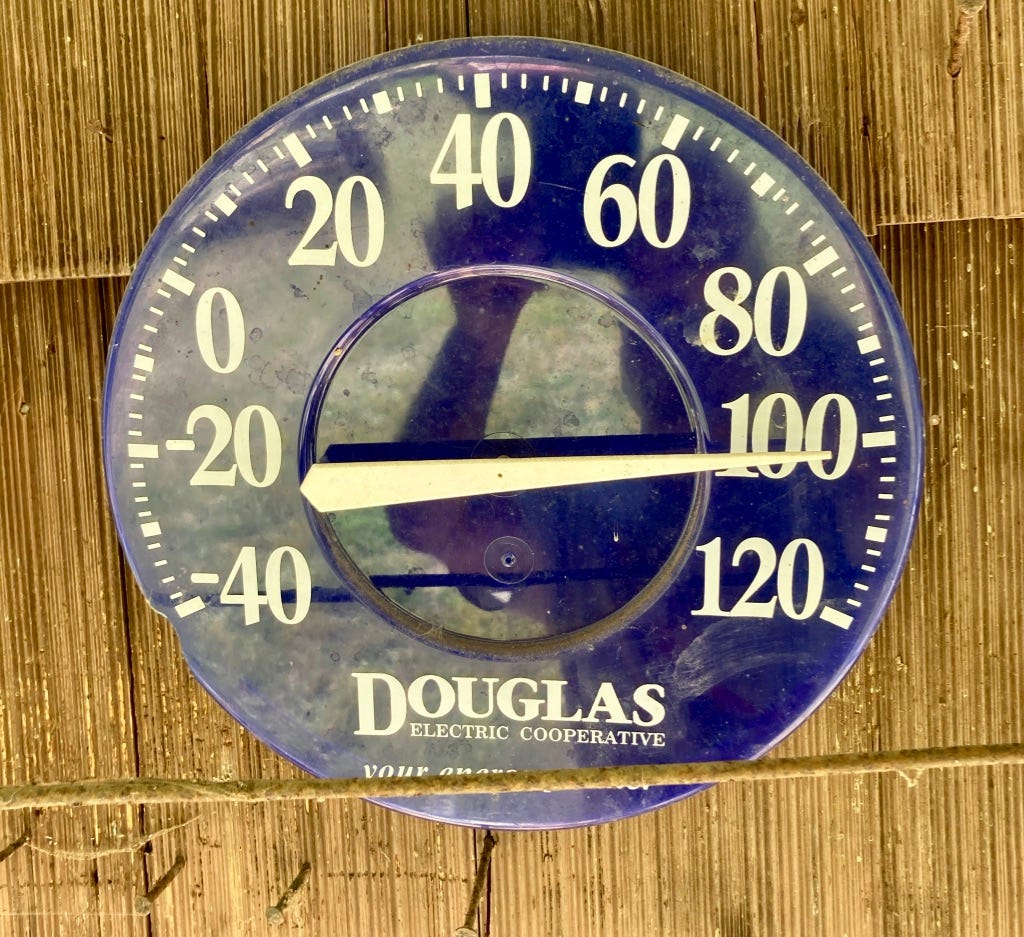

I emerge onto the front porch to find the Douglas Electric thermometer dialed up 102 degrees. Two acres of unmowed meadow are waiting. One more cutting should do it for summer. One more chance to keep the vegetation low to the ground in case it burns. I smear on sunscreen, pull on a particle mask, earmuffs, and finally a straw cowboy hat to keep the sun off my head, ears, and neck. The vibration of engine noise and whirling blades reverberates deep inside my chest. The Barn Swallows flee again, but I’m away from the garage quickly. Mole hills occasionally explode beneath the blades in billowing clouds of dust. An hour later three-quarters of the meadow is mowed. But even a fossil fuel slave with four-wheel mobility and rotary blades can’t save me from the heat. Eighty percent is a “B,” and like any sensible underachieving student I call it quits. Strip off my clothes. Grab a hose and run rivulets of tepid water over my body, flushing away sweat and mole hill dust and bits of clinging vegetation and a dried trickle of blood from a blackberry bramble that raked across my shin. The parched grass at my feet is grateful.

I wake from a second nap. Pick blueberries until Sun frowns off behind the western ridge. The temperature falls 20 degrees in an hour. I need to be home tonight, so after a quick stop to visit Martha I’m twisting along the ridgetops toward town. Night gathers the last evening shadows into her dark arms. Sun mellows into a mandarin band stretched above a black undulation of ridges, like the heat glow of newly welded iron, a transient connection between day and night. Headlights rove the still hot pavement, traveling between green palms of thimbleberry leaves and the gray courseness of second growth Douglas-fir trunks. My old trailer rattles behind the pickup with three small western redcedar logs scavenged off the road from last winter’s ice storm. Behind that a too-hot day dies away into darkness and the deep vat of history.

Muscle memory causes me to shift down to second gear for the familiar descent into the Siuslaw River Valley. Now the road coils and stretches, coils and stretches, the snaking pavement plying the darkness along the west side of Lorane Valley. Both windows are down. The accelerating air courses through the cab and over my bare arms like the warm hands of a restless lover. Suddenly a pool of cool air spills in the windows. Then another, and another, until they meld into uninterrupted frigid bliss. For a moment I consider rolling up the windows, and instead remember how utterly overheated the afternoon had left me. For maybe fifteen goose-bump minutes I’m not thinking about heat domes or fire warnings.

Then the road twists up the last ridge above town. The cab again floods with warm air. The night is too hot. Too early in the year.

This is powerful and visceral, with gorgeous meditations on the natural world in the midst of a cautionary tale. We've got our go-bags ready, and we're praying the forest doesn't go up in flames.

Tom, I followed over from your Facebook post to Substack. I will put you on my list of recommended sites as I am also writing stories here https://sandybrownjensen.substack.com/p/under-the-sign-of-the-red-horse